Exploring the Curtis family

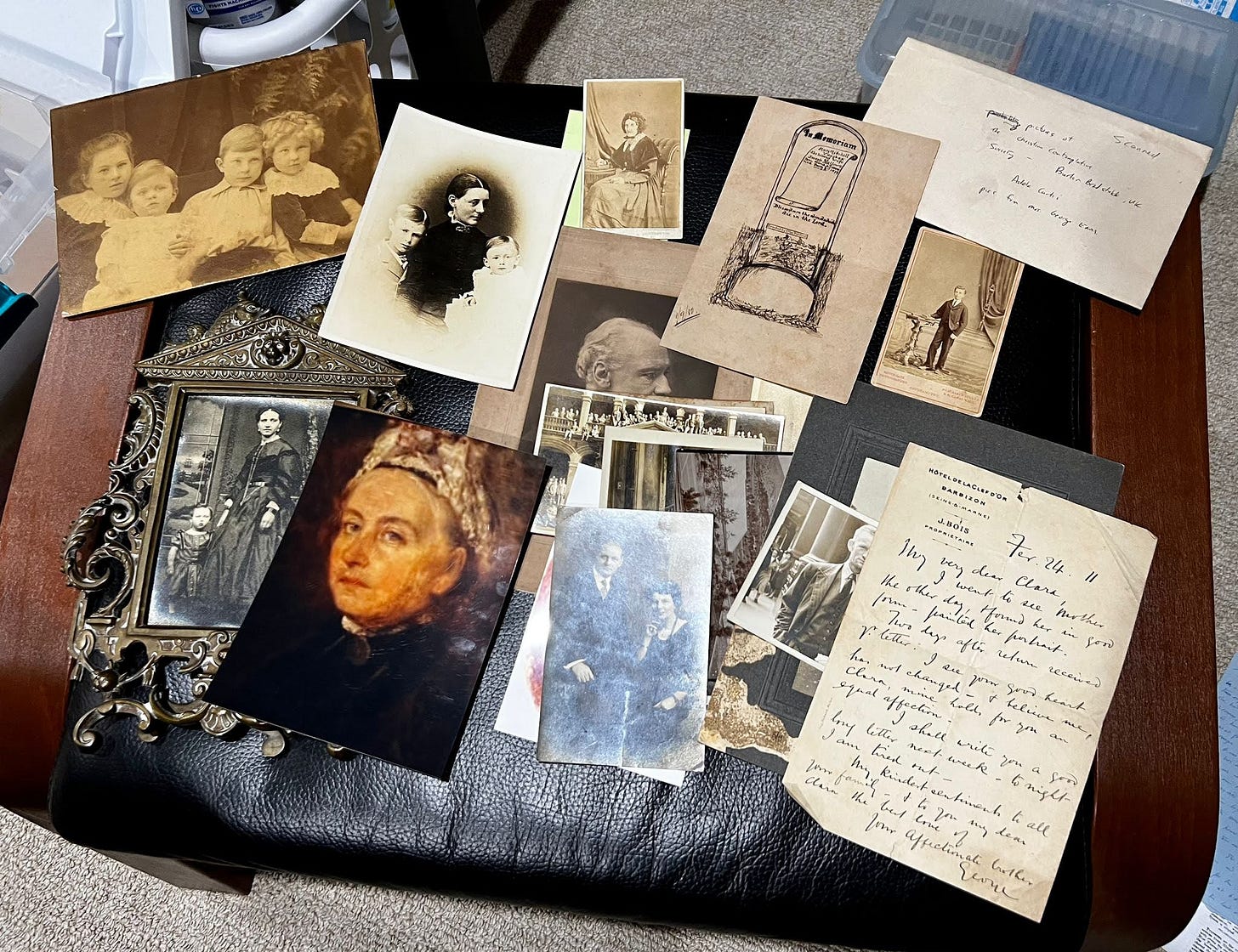

This is an edited extract from the blog originally posted on 22 October 2023 entitled ‘In Kansas City with Cabot and Betsy Sweeney’. I was able to spend time with Cabot and Betsy on my trip to the States in October 2023. Cabot has become the guardian of family memorabilia - a treasure trove of photos, letters and other papers.

It seems helpful to have the following information about Adela Curtis’ family background easily accessible on this site, rather than only tucked away in a blog post. I have added some more photos to this updated version.

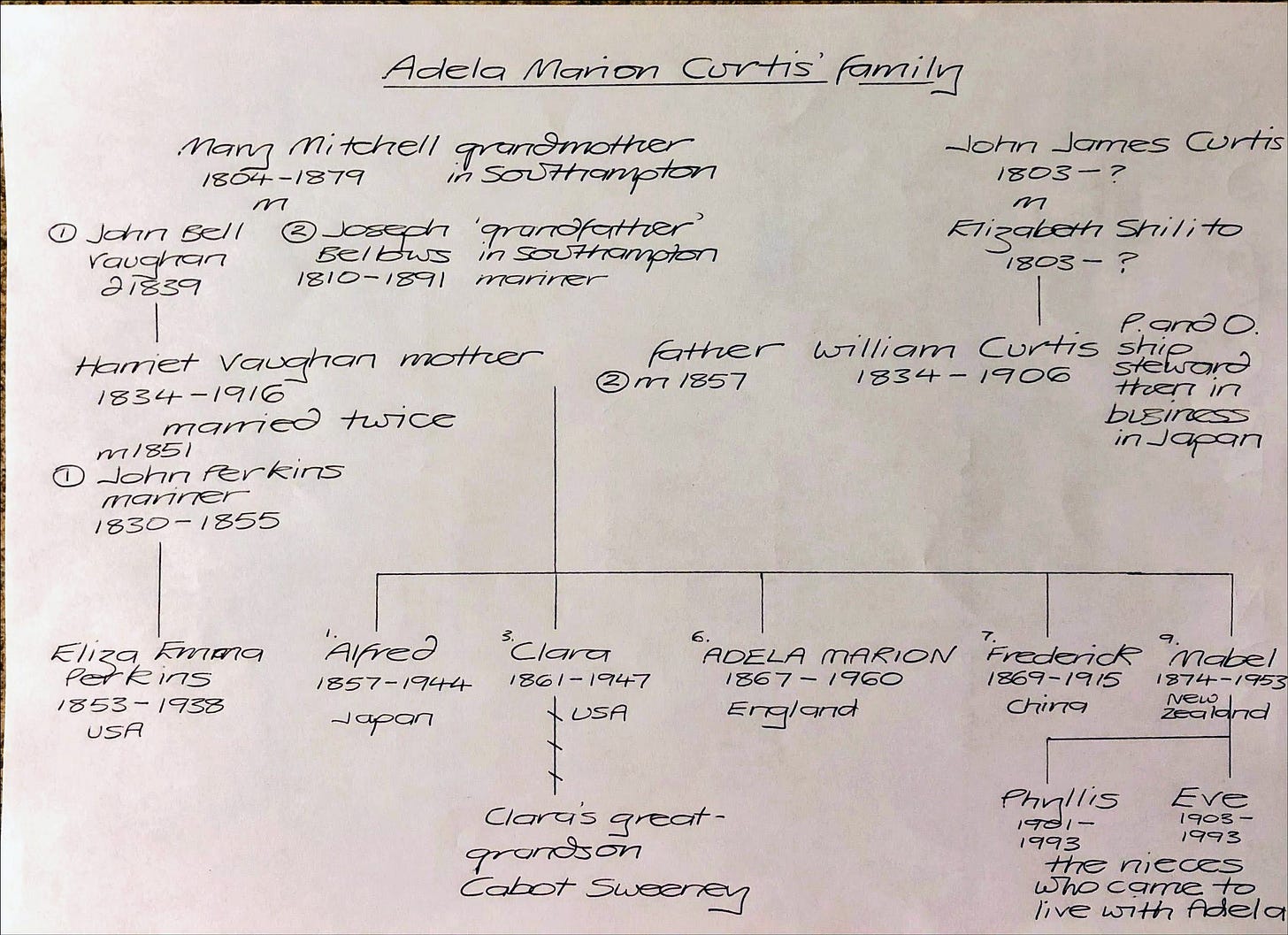

I thought it might be useful to have a simplified Curtis family tree to refer to, to illustrate this brief history of Adela’s family and early life. She was a sensitive child and I sense that her early life may have had a major impact on her personality and how she related to other people and to God.

Adela came from a large family. Her mother, Harriet Vaughan, was married twice and had a daughter, Eliza Emma, with her first husband, John Perkins, who died soon afterwards. Harriet and her second husband, William Curtis, were both 22 when they married in 1857 and they went on to have nine children together.

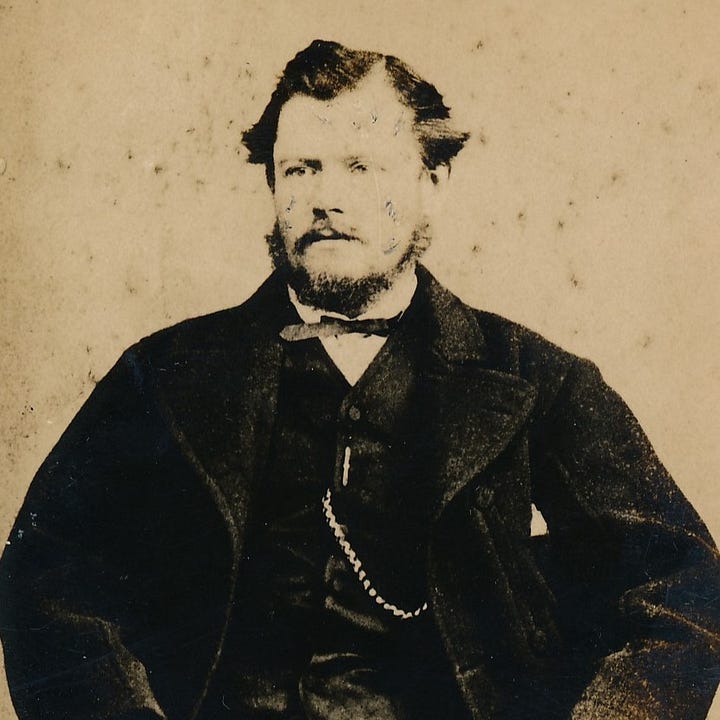

Adela's parents: Harriet Curtis nee Vaughan as a young woman; William Curtis aged about 32. For the first six years of their marriage, they were living in Southampton, with Harriet’s mother Mary and stepfather Joseph (and two of William’s brothers and their families) based in the same city. William and his two brothers worked as Ship Stewards for the P&O Shipping Line, so they would have been away from home for months at a time, but at least other family members were close by to give support.

This all changed for Harriet and William’s family in around 1863, by which time there were five children - Eliza Emma and four of their own offspring. William was ambitious and decided to relocate the family to Yokohama in Japan, where he bought a hotel and is said to have introduced ham into the country.

Yokohama was a rough and ready sort of place, with few women living there and no amenities for families. I can imagine that Harriet felt it was no place for children to spend much time in. Adela was one of the children to be born in Japan and they never experienced a settled home life. There were numerous journeys to and from Japan because schooling took place in England. However, Adela could remember being brought back to Southampton at an even earlier age. She was three and with her one year old brother Frederick, she was taken to live with foster parents called Barratt. She might have stayed with them for a couple of years. Her older siblings were all in boarding schools in the city.

On the one hand Adela minded being left behind by her mother - on the other, she had a significant spiritual experience when she was taken to an adult baptism service. This is what she said about it in later life:

‘When she was only four or five, [she] was taken by devout foster-parents to the Baptist Chapel in Southampton for an evening service of adult Baptism, at which a large number of men and women were immersed in a great tank sunk in the platform. The arduous climb for very short legs up the long steep flight of stone steps, the blaze of light inside the Chapel, the throng of white-robed figures standing on each side of the platform, the big golden beard and white hands of the black-gowned minister in the centre, the fervent hymns and prayers, the expectant reverence of the crowded congregation, the plunging rush of the water as each candidate was submerged, the mysterious reception of the dripping figure into an all-enveloping black cloak held out by waiting arms as it rose from the unseen depths… This made an indelible impression in the child’s soul of breathless awe and unspeakable wonder about “God” and although not one word or act of the service had been “understood”, the parable in action remained throughout life as an inexhaustible lesson on the mysteries of death and resurrection.’

As an adult, Adela did not find relationships with other humans at all easy. One of her youngest students, Nathalie Tingey, who was known as Sister Unity, wrote about her years later and said that she had one great friend, Lily Cancellor, who Unity described as her ‘alter ego’. Adela was the fastidious visionary, with a brilliant mind but with no human contact apart from Lily. By contrast, Lily was a warm people-person, whom everyone loved who met her and who could unruffle feathers. Adela had a very strong sense of God’s presence. I wonder whether her early life, with no settled family home, at least encouraged her withdrawal from humans and led to her focus and reliance on God.

Eventually the family split up - Harriet was not happy in Japan and she had returned to live permanently in England by 1881. I assume that she could not bear the separation from her children. Also her own mother Mary had recently died, removing any support she had been able to be to her grandchildren whilst they were in the UK.

As an adult, Adela’s sister Clara emigrated to the United States and Cabot is her great grandson. Clara is important in Adela’s story because they corresponded over a number of years and Clara kept 32 of Adela’s letters - a significant archive. I have seen scans of these before, but now I am able to handle the originals, thanks to Cabot’s care of them. From these letters we glimpse Adela’s life in Burton, from the late 1920s to the early 1940s. Mainly Adela is focussed on the present and future but the following passage from a letter dated May 31 1940 is significant because she expresses the bitterness she felt towards her mother when young but also how her feelings changed over time, as she came to understand more of her mother’s difficult life:

I have taken up my work as Warden again, after retiring & appointing deputies but danger seems to have given me a new lease of life as it did to our courageous mother to whom we all owe so much more that we ever dreamed when we were young. It took me many years to discover her wonderful qualities, & bless her for giving her 10 children such a high degree of health in soul & body. How often I have told her so, & begged forgiveness for the blind resentment I used to feel as a child, & the harsh judgement of later years before I began to understand the tragic facts of her life. She always smiles at me when I see her in the inner world, & I feel she is happy now, after the stormy waters of this outer existence.

Adela and Clara’s older brother, Alfred, also wrote to both sisters and again Clara kept some of his letters. (Adela destroyed any personal letters she may have received. She did keep two letters, written to her by Aldous Huxley!). Alfred’s letters to Clara are helpful to me partly because he often reminisces about their childhood in Southampton and partly because his Christian faith was important to him and he would often write about Adela and her books, of which he was sent copies. He lived all his adult life in Japan, starting out as a business man like his father and then going on to become a journalist. He died in 1944, by which time of course he had become an enemy alien living in a country at war with the UK. This brief quote is from a letter Alfred wrote in 1939 to Clara. (Addie is the family name for Adela):

The secret of Addie’s work – for which I shall, I suppose, always feel half tempted to envy her – lies in the fact that she saw and acted upon the self-denying, self-disciplining implications of the word before travelling very far along life’s highroad.

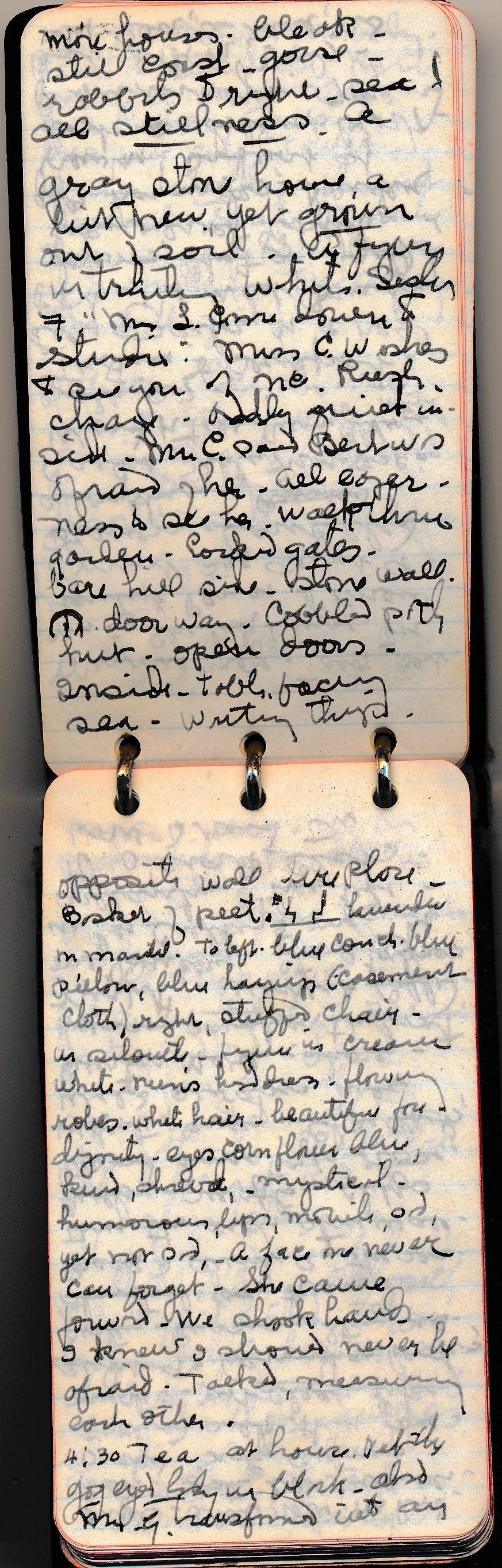

The exciting find! Cabot has a massive archive of family letters, photos and other memorabilia. Not all of them relate to the Curtis side of the family but towards the end of my stay in October 2023, he discovered, in a box relating to another branch of the family, a couple of travel notebooks about a trip taken to Europe, including the UK in 1928. One of those who travelled over was Clara’s married daughter Dorothy Lull (Cabot’s grandmother), who had arranged to stay with her Aunt Adela in Dorset as part of her trip. She kept a travel diary - the way it is written suggests that she was jotting words down as she went, rather than writing up her experience later in the day. We could imagine that she was making notes to jog her memory, so that when she returned to her family in the States, she would be able to go into a great deal of detail. Her mother Clara would no doubt be eager to hear about Adela, the sister she had not seen for almost fifty years - and whom she would never meet again.

The following is an abbreviated account of how Dorothy described her first ever encounter with Adela. (Some words are currently undecipherable and are omitted.) Dorothy is addressed as Mrs Lull; Adela is called Miss Curtis; Francesca acted as housekeeper to Adela when she first came to Burton.

July 27 (1928)

Train to Bridport… The West Country - downs, hedges, fields like velvet… gold hayricks - Maiden Newton - Bridport at last… Found taxi. Rode 4 miles… A gray stone house a bit new, yet grown out of soil… Sister F[rancesca] ‘Mrs. L[ull] come down to Studio. Miss C[urtis] wishes to see you… no rush…’ Great eagerness to see her. Walked through garden - locked gates - bare hillside. Stone wall. [here she draws an upside down horseshoe shape] doorway. Cobbled path - hut - open doors. Inside - table facing sea - writing things. Opposite wall fireplace - basket of peet… To left blue couch, blue pillow, blue hangings (casement cloth), right, stuffed chair - in silhouette - figure in cream white nun’s headress - flowing robes. white hair - beautiful face - dignity, eyes cornflower blue, kind, shrewd, mystical, humorous… old yet not old, a face one never can forget - she came forward - we shook hands. I knew I should never be afraid. Talked, measuring each other.

It is a vivid description. The fact that she says at the end of this extract that she ‘should never be afraid’ suggests that she came with some trepidation - no doubt Aunt Adela had quite a reputation in the family.

This picture shows Dorothy with a couple of companions on the ship in 1928 travelling from the US to Europe. Dorothy is in the white hat. Her travel diary may also shed light on the origins of the lovely pencil sketch of Adela Curtis which can be seen below. Dorothy was in London the day before she went to Dorset and after a lunch with Lily Cancellor, whom she intriguingly describes as Sherlock Holmes type, she notes, ‘On route to Penn? - knew I must see Aunt A. drawn - cancelled everything - called Sister Francesca. Went for taxi - ? Globe Hotel’. Is this how the pencil sketch found its way to the States? Did Dorothy tell Clara her mother about it and they decided to purchase it? It has been a mystery as to how the portrait ended up in the possession of Clara’s family in the States - perhaps this brief reference in Dorothy’s travel diary points to a solution.