Exploring Mysticism - making connections ...

... and introducing some of Adela Curtis' followers

A warm welcome to this post on a chilly November day. Firstly, I want to flag up some additions to this website in case you haven’t seen them - I have added two pages to the navigation bar at the top, one entitled Who was Adela Marion Curtis?, which is an edited version of one of my earliest blog posts. The second is called Exploring the Curtis family, which is drawn from a post I wrote whilst staying with Cabot and Betsy in the States. It seems sensible to have these brief introductions to Adela Curtis’ life and family background in a place where they can be accessed easily. I will add further pages when the need arises. So, thinking about today’s post - why the focus on mysticism? It is an important topic for New Thought and for Adela Curtis - but I also sense that mysticism is becoming an area of spirituality which a growing number of people are turning to these days, including those in more mainstream Christian faith traditions. I begin below with a bit of my own journey into mysticism, which has taken form particularly since I have come to live and work at Othona. And also - Who were Adela Curtis’ followers? An area of research I hope to look at in these blogs on a regular basis is that of Adela Curtis’ supporters. Some people committed many years to following her and to taking up the way of life she advocated - I have been curious about them for a long time and am delighted that I have been able to find out who those commemorated in the chapel at Othona were, for example. This post includes a spotlight on Mary Goodwin, nee Cook. She has a memorial in the Chapel and interestingly two of her siblings, Margaret Christian and Ann Eliza, were also followers of Adela Curtis at some stage during the School of Silence years (1907 - c1919). And finally, early notice of a residential weekend I will be leading at Othona, 20 - 23 June 2024, on Adela Curtis and which will include discoveries from my trip to the States. When bookings are open for this, I will paste a link to the Othona website in a post here, in case you fancy joining me in person then!

Beginning to Explore Mysticism. I have described in earlier posts about our practice here at Othona when we gather in Chapel - and how after our opening words, someone will often read a passage or a prayer from one of a number of books we keep handy. I started to realise how drawn I was to a few of these, such as Praying with the Earth: a Prayerbook for Peace, by John Philip Newell, who at one time was Warden of the Iona Community. This book arose out of his friendship with a Jew and a Muslim and their journey to find ways of praying together. This is an example of the type of prayer he composed:

At the beginning of the day

we seek your countenance among us, O God,

in the countless forms of creation all around us

in the sun’s rising glory

in the face of friend and stranger.

Your Presence within every presence

your Light within all light

your Heart at the heart of this moment.

May the fresh light of morning wash our sight

that we may see your Life

in every life this day. [p42]

One of the main characteristics of mysticism as I understand it is the sense of the oneness of everything; eg the oneness of God and creation; the oneness of humanity and God. There is a quotation associated with Mother Julian of Norwich: ‘Between God and the soul there is no between.’ (One of the words Julian used in her Revelations was ‘oneing’ to describe the relationship between God and human.) Many of the prayers in Praying with the Earth by John Philip Newell seem to me to come from within such an understanding - ‘Your presence within every presence, your Light within every light’ - as an example. This isn’t prayer that senses a barrier to God, or needs to get God interested in the pray-er or creation. It is the kind of prayer that seems to lead naturally into silence and meditation. I was becoming aware of my own preference for this type of prayer, without putting a name to it, at the same time that I was beginning to research Adela Curtis, who was routinely described as a mystic. Indeed, according to her neices, Aldous Huxley was said to have called her, ‘the one living mystic in England’.

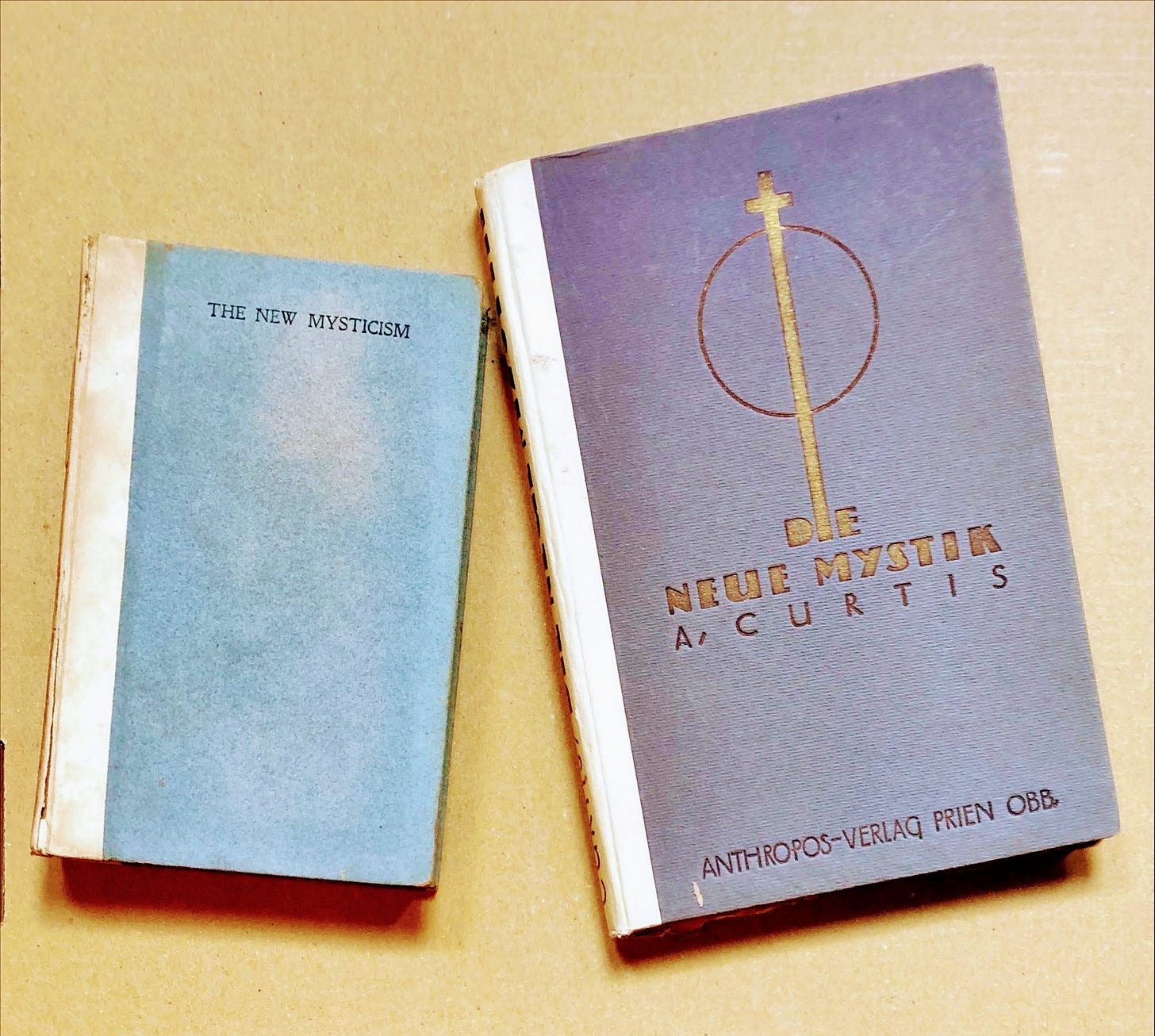

Adela Curtis and mysticism. Adela’s initial major publication was her book called The New Mysticism, which first came out in 1906 and went through a number of further editions in the following years. In this, she set out to introduce New Thought to the British and she began by giving her definition of a mystic as, ‘one who seeks for direct knowledge of the Creative Principle’. She deliberately used ‘Creative Principle’ rather than ‘God’ because she claimed that this broader description would be acceptable to everyone, not just those who were comfortable with God language.

For, whether we are aware of it or not, at some time in our lives, consciously or subconsciously, we all want to know whatever there is to be known about our origin and our destiny. So, we are all mystics, and as such it is worth our while to know the latest discoveries in this universal search for the Source of Life, Knowledge, and Power. [p2]

And in keeping with New Thought understanding, she argued,

We have so long looked outward instead of inward for all we have wanted, that we cannot at once realise God and His whole Creation as within us.

The important biblical phrase, one of Jesus’ own sayings, which Adela and other New Thought writers often referred to was, ‘The kingdom of God is within you’. Because of this, Adela could state that even if all scriptures were destroyed and all religious leaders removed,

There is left within us that Principle of Being from which all these came forth; and if we know our Principle we can create for ourselves all that ever has been, all that ever will be.

Richard Rohr, the Catholic Franciscan and founder of the Center for Action and Contemplation, is a great advocate for having an awareness of the connectedness of all things. And in his Daily Meditation for Thursday this week, he says that Western civilization has paid a heavy price for its separation from the natural world, but probably is not aware of it. He refers to St Francis as a positive example of someone who experienced connectedness with other parts of creation.

New Thought mysticism has distinct aspects to it and Adela refers to some of these in The New Mysticism, as she seeks to explain the value of this particular approach to her readers.

Adela (along with other New Thought (NT) practitioners) was critical of the traditional churches, for failing to take seriously Christ’s promises about how his followers would do what he had done, such as healing people. Instead, for centuries the church had been resigned to the suffering and poverty it had found in the world. She gave a striking example of both St Francis and the Buddha, renowned and admired within their own faith traditions for turning their backs on wealth. However, from her NT perspective, they were seen in a much dimmer light because wealth and success, as well as good health, were to be redeemed and embraced as positive goals of life. She did not see Francis and the Buddha as examples to follow, because from a NT perspective, it is not spiritual to be poor.

Adela demonstrated this contrast between traditional church thinking and New Thought in The New Mysticism where she imagined ‘Europe’, (in other words the traditional church) claiming that their emphasis on suffering was right because ‘Jesus suffered, Jesus was poor, Jesus died’. On the other hand, ‘America (that is, NT) says,

"Jesus Christ healed the sick, raised the dead, found His tax- money in the mouth of a fish, fed nine thousand people on twelve loaves and a few small fishes, proved that no violence could destroy His power over His body, and said to His followers, 'He that believeth on Me, the works that I do shall he do also; and greater works than these shall he do; because I go unto the Father.' Did the Christ suffer? Was the Christ poor? Did the Christ die?"

This distinction between the earthly Jesus and the spiritual Christ is another key part of New Thought thinking: Jesus was not ‘Christ’ from birth but grew into being Christ. From this it was argued that everyone could become Christ and do the things that he did, just as he had promised. From an NT perspective, therefore, Jesus Christ is the supreme example of what is possible for everyone to become, rather than the exceptional one. (When I was with Merry and Rob and we were in Houston, someone from that Center for Spiritual Living told a humorous story against themselves: they had been at an event and someone said to them, ‘Oh, you are one of those who believe they are God’. The CSL person replied, ‘It’s worse than that, we believe you are God as well!)

A further key aspect for Adela was linked with evolution and the belief that humanity was evolving into a higher form of consciousness. I will look at this in more detail in another post. For now, I find myself reflecting on the fact that Adela was arguing for her listeners and readers to consider New Thought, not because it was just an interesting theory, but because, like many of the key NT leaders, she had experienced healing herself through the ministry of another NT healer. This was evidence for her that backed up the claims of NT. It was this way of seeing God and how humans might operate in the world that formed Adela into the minister she was, as healer, teacher and leader in meditation.

At the bottom of this post I have put some information about resources for exploring mysticism further, if you are interested.

Introducing Sr Mary and her siblings, Srs Christian and Veronica

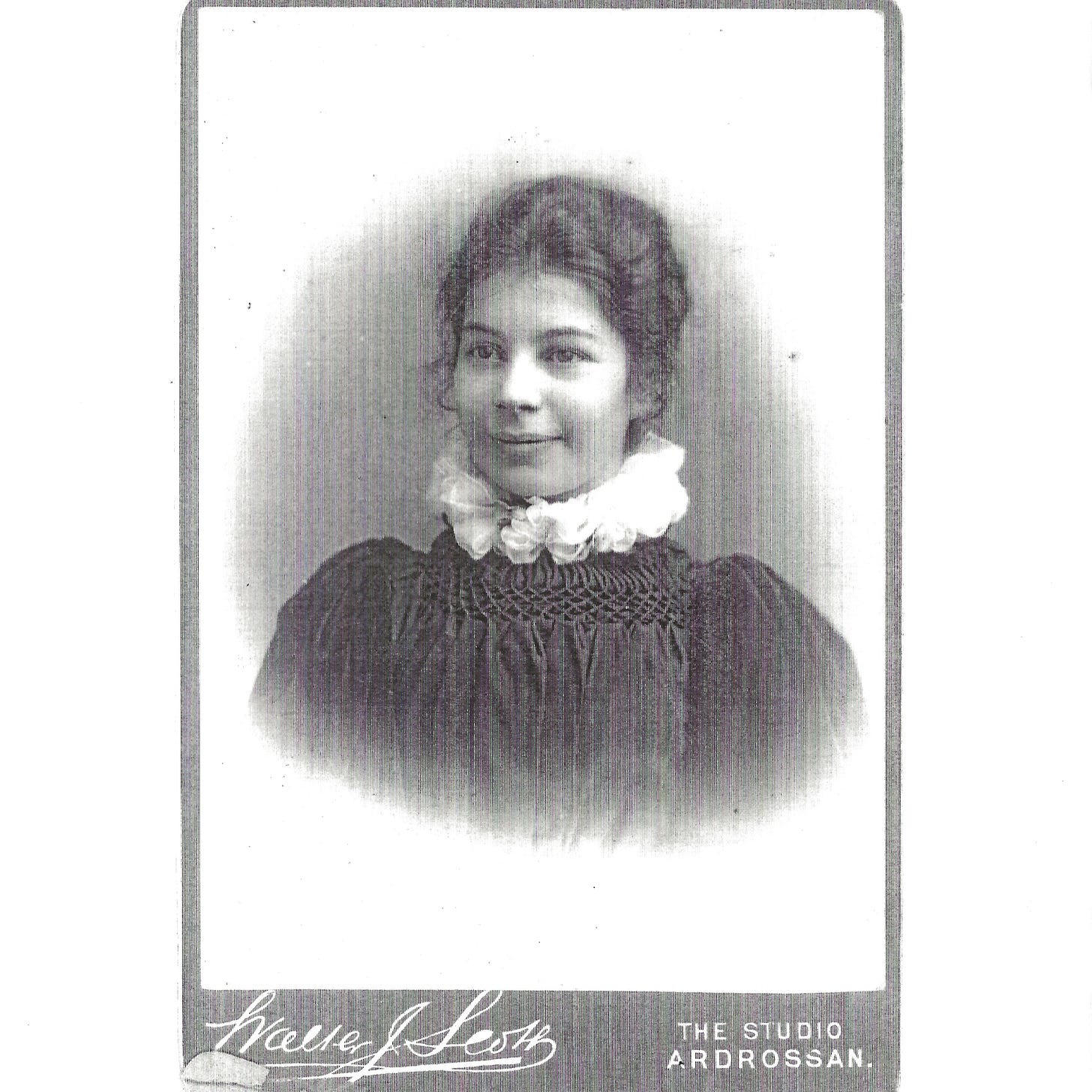

Mary Cook (1875 - 1950) was one of seven siblings who grew up in Saltcoats, Ardrossan, a town in Ayrshire, Scotland. Their father was a law and bank agent. Her middle class family background was fairly typical of those drawn to join Adela Curtis’ communities. Mary’s older sister, Margaret Christian (known as Sr Christian) and younger sister Ann Eliza (Sr Veronica) were also involved in the School of Silence in London and Cold Ash, Berkshire. Sr Unity knew them then and wrote about them many years later, in her characteristically generous way:

‘Three Scots, all outstanding personalities, entirely different from each other. Christian was an artist in the process of illustrating Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass”. (I have a copy of this.) Robert [Sr Unity’s husband] and I purchased six originals from her and I still have five, the sixth having been lost in the Blitz. Mary Goodwin may have been the eldest of the three – she was the only one who went with the Community to Burton Bradstock. I have no idea what happened to Christian and Veronica. Veronica was a great character with a fine, contralto voice. Very good to me and the one I remember most vividly, partly because of her fearless nature, great sense of humour and clarity of vision.’

If you are interested, have a look at examples of Sr Christian’s artwork for the Walt Whitman book mentioned above.

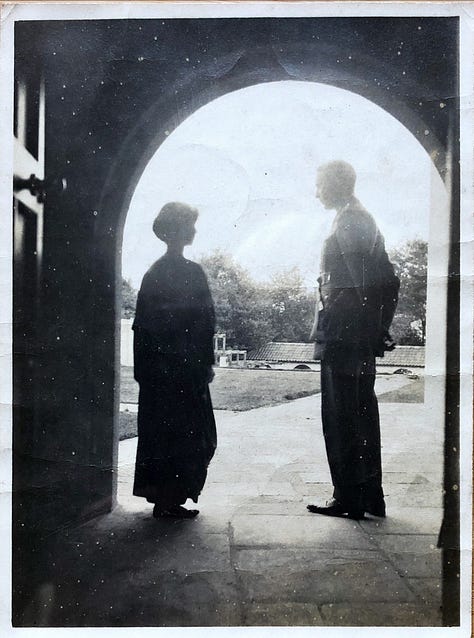

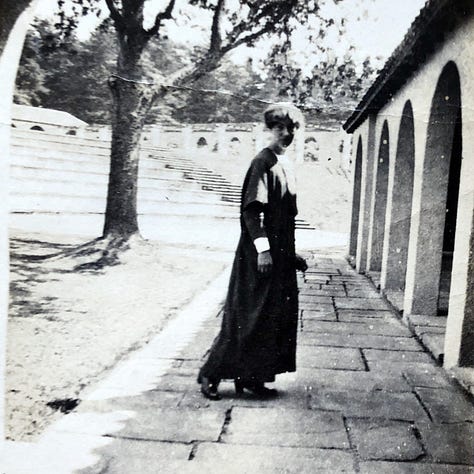

Mary married Ernest Goodwin in 1909 when she was 34 and he was 32. They did not have children. They were both on the General Council of the School of Silence in 1914 and there are a number of photos taken of them at Cold Ash.

Sadly the marriage had foundered by the early 1920s, when Ernest had a child with another woman. Mary and Ernest divorced, he married the mother of his child and they went on to have a number of children together. Very interestingly, one of these children remembered meeting Christian and Veronica when they were playing in an orchestra at a pantomime and they sent tickets for Ernest’s children to attend. (It was one of Ernest’s grandchildren who told me this story. It would seem to suggest that eventually there weren’t bad feelings between the two families. Likewise, it was Ernest’s family that had kept the picture of Mary as a young woman in their possession.)

I would not presume to guess why the relationship between Mary and Ernest fell apart but I think it is relevant to reflect on what impact some of Adela’s teaching might have had generally on the married members of the community and on those who desired a sexual partner. In an article which was published in 1919, called Of the Peace of Littleness in Sleeping, Adela argued that the desire that the opposite sexes experienced for one another should be transmuted, in other words, its direction should be altered so that it is focussed on God instead. This could happen, she wrote, if a person were to,

Listen to the Word with all your heart, with all your mind, and with all your strength, and you will hear that it does not tell man to deny his desire, but rather invites him to change its direction. The Lord of the body says ‘Come unto Me and I will give you rest’. Look with open eyes at man’s desire for woman, and at woman’s desire for man. What is it that each is really seeking? Rest, Comfort, Beauty, Peace, Perfection, Wholeness, Joy, Infinity, of Life and Love. These heavenly states of feeling can only come to the soul by inspiration from the Divine or Superconscious Self within. [Italics and Capitalised words are Adela’s own.] [pp30/31]

Adela was almost certainly naturally ascetic in nature and I am not aware as yet that other New Thought teachers advocated this approach. This was probably part of her own particular teaching, which in general was demanding.

Mary lived in the community at Burton Bradstock and for a time in the 1930s she was in charge of the main house and known as Warden Emmanuel. When Lily Cancellor, Adela’s greatest friend, died unexpectedly at the end of 1938, it rocked the whole community. Adela struggled without Lily, the people-person, to smooth things along and in the early Spring of 1939 she demoted Mary from her role in the house because she seemed to have no energy for it. Mary had also been close to Lily and it is likely she was grieving or perhaps depressed as a result. Later in the year there was a big falling out between Adela and most of the sisters, after Adela discovered that supplies of tea, which had been bought as emergency stores in case of war, had been consumed by the community. Mary withdrew to her hut for a while as the dust settled. She remained part of the community during WWII and eventually died in 1950, one of the last to live on site.

Further Resources for Exploring Mysticism. I have found the following resources helpful.

Wisdom of the Mystics. If you are interested in delving more into New Thought and mysticism. When I met with Revd Kathy Mastroianni at the Science of Mind Archives near Denver, she flagged up these recorded zoom sessions which are freely available on their website. A number of important New Thought people, plus others including Richard Rohr, are the subjects for discussion.

Turning to the Mystics. If you are interested in learning more about some of the medieval mystics, and how they can resource us today. James Finley is one of Richard Rohr’s colleagues at the Center for Action and Contemplation (CAC). He has recorded these free podcasts on people such as Julian of Norwich and Meister Eckhart.

Internet Archive. If you want to read the actual books, many old texts, including the first edition of Adela Curtis’ book A New Mysticism, are freely available to read on this website.

Sarum College, which is based in Salisbury, Wiltshire in the UK, has offered a couple of series of short online courses on Modern Mystics this year. There was a small charge for these. Their website would give details of future courses.

The Celtic Wheel of the Year by Tess Ward is another lovely book of prayers we use at Othona and which have a mystical element to them. This book draws on the Christian tradition and earth based spiritualities.

The Poetry of Mary Oliver. She has been described as a modern mystical writer.

Fascinating and enlightening, Liz. Another wonderful and beautifully written post which helps some more puzzle pieces fall into place regarding my own spiritual path and why I was drawn to Othona! Thank you again x