A warm welcome to the latest edition of In Search of Adela Curtis, a Modern Mystic. When I read biographies, it is always the childhood of the person in question I am first drawn to - what was this person like as a child? What were the circumstances of their life when young? What might be seen of the child’s experience reflected in their later life? This has been true for me about investigating Adela Curtis too. So one of the areas of research which has fascinated me recently has been discovering more about her birthplace and first home, the city of Yokohama in Japan. I was quite ignorant about its development from a small fishing village into an international city, until I began digging into its history. And for my research into Adela’s life, there is also the highly significant experience of her and her little brother being taken from Yokohama by their mother when Adela was just three, to live with foster parents in England for more than a year. This could not have been a decision taken lightly by her mother…

[I have discovered a couple of helpful resources that shed light on life in Yokohama in the 1860s and 1870s, the period in which Adela would spend part of her childhood in Japan. The first is a book written in 1909, Japan Gazette Yokohama Semi-Centennial, specially compiled and published to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the opening of Japan to foreign trade [JGYS-C]. The second is a history of the Anglican church in Yokohama, The Church on Colonel’s Corner [CCC] written by Revd Eric Casson in 1962, (with a later addition by Revd John Berg). The church has kindly allowed me to share photographs from the book in this post.]

A Pioneering Family

As I’ve mentioned in an earlier post, Adela came from a large family - she was her mother’s seventh child. Her mother, Harriet Vaughan was a widow with a young daughter, Eliza Emma, when she married her second husband, William Curtis in 1857. They were both 22 and they went on to have nine children together.

For the first six years of their marriage, they lived in Southampton, the place where Harriet had grown up. She had her mother Mary and stepfather Joseph living nearby, as well as two of William’s brothers and their families based in the same city. William and his brothers worked as Ship Stewards for the P&O Shipping Line, so they would have been away from home for months at a time, but at least other family members were close by to give support. William must also have been doing reasonably well financially, as they had two live-in servants in the early 1860s. We can imagine that for Harriet, who had experienced poverty in her own childhood after the early death of her father, this stability and support network were important to her.

However, that stability was disrupted for Harriet and family in around 1864, by which time there were five children - Eliza Emma and four of their own. William was clearly an ambitious young man and someone willing to take risks with a view to making money. Through his travels with P&O, he would have become aware of the developing situation in Japan. For centuries the country had maintained a policy of strict isolation towards the West but this changed in the late 1850s, when the American fleet put pressure on Japan to open its borders for trade and sign a treaty, which it did with great reluctance. William, who had grown up in an inn in Gravesend in Kent, decided to purchase his own hotel but this one was on the other side of the world. He relocated to Yokohama, where the treaty allowed for foreigners to settle and he became just the second owner of The Commercial Hotel. Later he would take on another hotel and engage in trade and is said to have introduced ham into the country, sharing the secrets of its making with the Japanese. Curtis family lore says that he made more than one fortune but lost money as well.

So in 1864, William and his family became pioneers, and one consequence was the splitting up of the family unit because the older boys (and most likely the older girls too) didn’t go out immediately, as their mother placed them in a boarding school in Southampton. Their children were to receive an education but this would require trips to and fro between Japan and the UK and the sea journey could take between four and six months to complete each way. This was to become the pattern for family life from now on: one of the older children as an adult commented that from then they were never all in the same place at the same time.

Yokohama in the early days

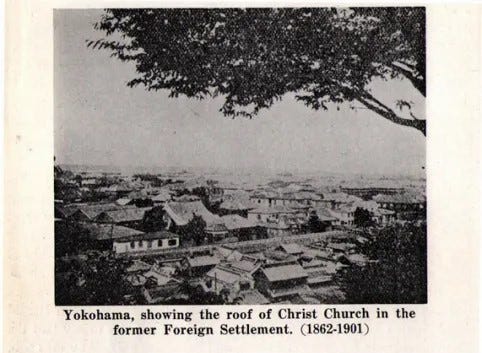

The Curtises were some of the first Westerners to move to Yokohama. It had previously been a small fishing village but by the time they arrived, it was much larger and clearly segregated into two sections, as seen on the plan below.

On the left hand side, with all the lots numbered, was the Foreigners’ town with narrow streets and on the right the Japanese town highlighted in green. The likely site of the Commercial Hotel is coloured navy blue. Above it in orange is Christ Church and the Parsonage, where the first Anglican chaplain, the Revd Michael Buckworth Bailey lived. The blue line indicates water, with the sea at the bottom of the plan. On the foreigners’ side the sea would have had numerous vessels in it, protecting the Western inhabitants and their trade. One early resident was struck also by the presence of soldiers in the town, describing Yokohama as being like:

‘a large international military camp, the presence of British and French military forces here being due to the antipathy displayed towards foreigners by the Japanese.’ [JGYS-C p60].

(On the plan, the troops were stationed in the area marked in brown until 1874. Every Sunday morning they would march through the town to the church to attend the service.)

That antipathy led the British Consul to give a public warning in Yokohama, ‘It is desirable that the greatest caution and prudence be observed by British Subjects in visiting the surrounding country.’ [CCC p8.] The treaty drawn up in 1858 allowed the foreigners to travel within a 30 mile area beyond their settlement, but this was proving dangerous.

Another resident who arrived in 1869 did not like the town, writing about ‘Its roads and its ugliness’ which were ‘like those of an American prairie or Australian bush town’ [JGYS-C p39.]

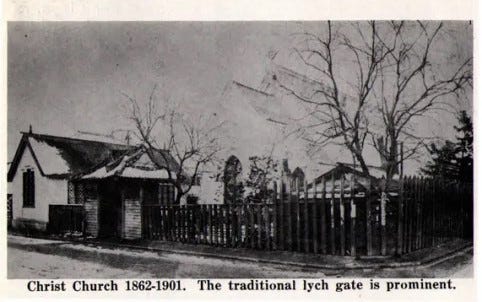

The Anglican church was completed in 1864, the same year that William Curtis arrived and it was designed outside and in to give the British the impression of being back home.

However, no matter what the building looked like, the situation was in complete contrast to what might have been experienced in the UK. The hostility that the Japanese felt towards the West went back centuries and in particular their antipathy was historically towards the Christian faith. Japanese nationals were forbidden to practice this faith and it was only by a clause inserted into the treaty that Westerners were allowed to build churches and hold services on Japanese territory. The first Chaplain had to face questioning by Government officials and he was required to have a bodyguard of Yaconin warriors who carried two-handed swords. [CCC p6.]

In March 1866, a new Curtis baby, James, was born to Harriet and William and he was baptised in the English church. Later that year there was a catastrophic fire which started in the Japanese town and spread to the foreigners’ settlement, with the result that about half of the buildings were destroyed. (All the buildings then were wooden, so fire was a constant risk.) The Anglican church escaped the fire, as did the Commercial Hotel, but it must have been a very frightening experience for all.

Adela was the next Curtis child to be born in 1867 and then another son Frederick in 1869. Harriet may well have felt that Yokohama was a quite dangerous and unwelcoming place for young children because of the events related above. In addition, there are questions about what kind of ‘home’ the hotel would have provided the family: it was remembered by one early resident of the city as a ‘quite third rate’ establishment [JGYS-C p56]. It was probably a combination of factors that led to these two little ones being taken by their mother to England on a P&O vessel when Adela was three. They were placed as ‘nurse children’ with a foster mother in Southampton, whilst most of their older siblings were in boarding schools in the same city. Adela remembered being left behind in this way. Perhaps Harriet’s decision to leave even her smallest children behind is not so surprising, from the description of the conditions in Yokohama in these early days. However it must have been exceedingly difficult for their mother as she came to feel that Adela and Frederick were better off living with foster parents half way across the world, than with her.

Some of the Ways in which Yokohama had an impact on Adela’s life

One of the obvious effects of the move to Yokohama was on home life. How much the hotel felt like ‘home’ is hard to say. There is no doubt that Adela’s relationship with her mother was damaged and the early, prolonged separation would have been a big factor. She wrote how resentful she had been towards her mother because of her childhood experiences. She would also describe her mother as being detached from her children: perhaps that was how Harriet survived the ruptures caused by the pioneer way of life.

What is intriguing is Adela’s responses to her father’s approach to life. She did spend some of her childhood in Japan and would have experienced her father and other Westerners operating as the capitalistic trading pioneers and risk-takers that they were. Her reactions to this are interesting:

On the one hand she was to turn her back completely on this capitalist approach to life. She often denounced it in her writings - she would give an example of the way workers on the other side of the world were oppressed so that comfortable middle class British people could enjoy their leisurely lifestyle. Her passion for self-sufficiency and thus not being a burden on anyone was partly fuelled by this.

Alongside this, when she and Lily were running their bookshop in the early 20th century, Adela wrote a long and favourable review of a book written by a Westerner who went to live in Japan. He did not go to trade, but quite the contrary, for he went to learn from the Japanese about their way of life. He too had some negative things to say about merchants and bankers which Adela quoted at some length in her review.

On the other hand, Adela too shared the risk taking ‘gene’ which had taken her father and the others like him to Japan, where every venture was new. For her, I think it found expression through her taking hold of New Thought, and its positive message which encouraged people to create the life they wanted, rather than be held back by their upbringing or family background. She was a pioneer in the way she set up communities, outside any traditional institutional structure and she took financial risks and certainly as a result of the failure of Cold Ash, lost a good deal of money.

She was an outsider in middle class England because of her birth in Japan and her childhood experience. This may be more conjectural but I think it could have been this outsider’s perspective which enabled her to see what she believed was wrong with life, as it was being lived by the comfortable middle classes. These were the people she was associating with and wanted to influence. I don’t think she grew up with a sense of entitlement - if she had it might have been far less likely that she would have stepped away from conventional living, to open up a vision for herself and others of a different, potentially more meaningful and purposeful way of being.

Thank you for such a fascinating and detailed research into Adela's background, and the context of empire and international trade in which she grew up. I wonder if in later posts we will be hearing about Adela's attitudes to empire and issues such as Indian independence and the spirituality of Ghandi and interfaith approaches to spirituality developed by missionaries and thinkers like CF Andrews?

Thank you, Liz, for this most interesting background to Adela’s life - I had no knowledge of British involvement in Japan in the late 19th century. You’ve shone a light on that. Good to have the photos of family and the church in Japan too. Wishing you well, Sue