Turning an Ambitious Vision into Reality - The School of Silence

in Kensington and at Cold Ash in Berkshire

A warm welcome to all readers, and particularly to those who have recently joined me here, In Search of Adela Curtis, a Modern Mystic. If you would benefit from a brief overview of Adela’s life and work, do click on this link. Today’s post focusses on Adela’s School of Silence, which was in operation from 1907 - 1919/20. She pinned her hopes on its success and its eventual failure hurt her deeply and almost certainly contributed to a breakdown.

At the end of the post I share some words from Howard Thurman, a 20th century African American theologian and mystic. These are words that inspire me in my life and research.

Establishing the School of Silence in Kensington

After receiving four years of New Thought teaching from Dr James Porter Mills, Adela began her own centre for meditation, teaching and healing in 1907 and she called it The School of Silence. New Thought (NT) was a movement that encouraged individuals to make their own mark and spread the message in their own way, rather than necessarily remaining as a disciple to their original teacher. Adela was following the pattern of many NT practitioners, therefore, and it is highly likely that Porter Mills encouraged her to develop her own vision and practice, as he had done himself. She started the School in her own home, a former artist’s flat in Pembroke Gardens in west London - it was basically a studio with small living quarters attached.

The School was established for the purpose of

‘studying the life and words of Jesus Christ by the Way of Silence or Creative Meditation upon the Divine Word for the regeneration of Soul and body and the attainment of the Spiritual Consciousness or Christhood.’

Why did Adela call it the School of Silence? She was not intending to set up a church - teaching is a key aspect of the NT movement, hence the decision to name her centre a school. And regarding silence - she spelled out the importance of silence for her in the book she wrote at this time called The New Mysticism

‘a few… have discovered an order of silence more powerful than any form of mental suggestion. These do not affect the soul by means of any thought, feeling or action; but by the law of Unity which tends to lift all minds to an equal level of enlightenment, they are able to bring those who are in subconscious sympathy with them, into union with the Spirit or Principle of Life which is One in us all.’ [p60 her italics]

This meant that in practice, her healing sessions, which usually lasted 15 minutes, were entirely silent. No touch or spoken word was needed because this way of healing focussed on the minds of the healer and the patient ‘coming into union with the Spirit or Principle of Life…’ It had been in such a healing session with her New Thought teacher, Dr James Porter Mills, that Adela had experienced healing of her own ailments. This type of ‘mental cure’ was a key aspect of the NT movement generally.

As the numbers of participants at her teaching, healing and meditation sessions grew, so the studio must have become cramped. In 1910 she was able to move to a much bigger property, 10 Scarsdale Villas, which was about a 10 minute walk away. A few years later, the house adjoining (number 12) was added to the School, and then in 1913, a club was started for paying members. This Students’ Club, which was open 10am – 10pm daily, offered three simple meals a day, plus facilities which included a common room, a library, two dining rooms and kitchens, 8 bedrooms and a garden, plus a class-room which could be used for music, dancing, lectures or debates, as well as for the usual teaching and meditation sessions. So the Club meant that the work of the School could be more accessible to those who lived outside London because they could stay on the premises for a period of time if they wished. It would not have been cheap to do so - the clientele would have been from the middle classes.

This might have been ambitious enough for some people, but Adela’s vision for her work was larger still. Her desire was to establish a residential centre outside London and unlike Scarsdale Villas, where the School had to adapt to the premises, this was to be a brand new purpose-built construction. In the new context, Adela wanted to combine the work of the School in meditation and healing, with a long held dream of hers to prove that it was possible to live a self-sufficient life. She minded greatly that many people were oppressed around the world, so that for example, the middle classes in Britain, could live comfortable lives as ‘parasites’ upon the labours of others. She believed that living self-sufficiently was the answer, so there were to be extensive classes that would help students learn a range of skills, including how to grow their own food and make their own clothes. She recognised that

‘where one man or woman working alone can scarcely do more than heroically starve, twenty men or women working together can have a satisfactory life.’ [The School of Silence Prospectus, (May 1913) 14]

How was all this to be financed? The fees that the students had been paying for the sessions they attended at the School were put towards the development of the work of the School. Also, according to Phil, Adela’s niece, her aunt was a wealthy woman in her own right at this time, but she didn’t say where that wealth came from. Presumably her writing was providing some income and her own needs in terms of clothes and food were not large. However, Phil also said that these bigger plans Adela had in mind for a Settlement were beyond her own means and she formed a group of trustees from amongst the students, who also contributed towards the costs of the buildings on the new site.

Turning a dream into reality at Cold Ash, Berkshire

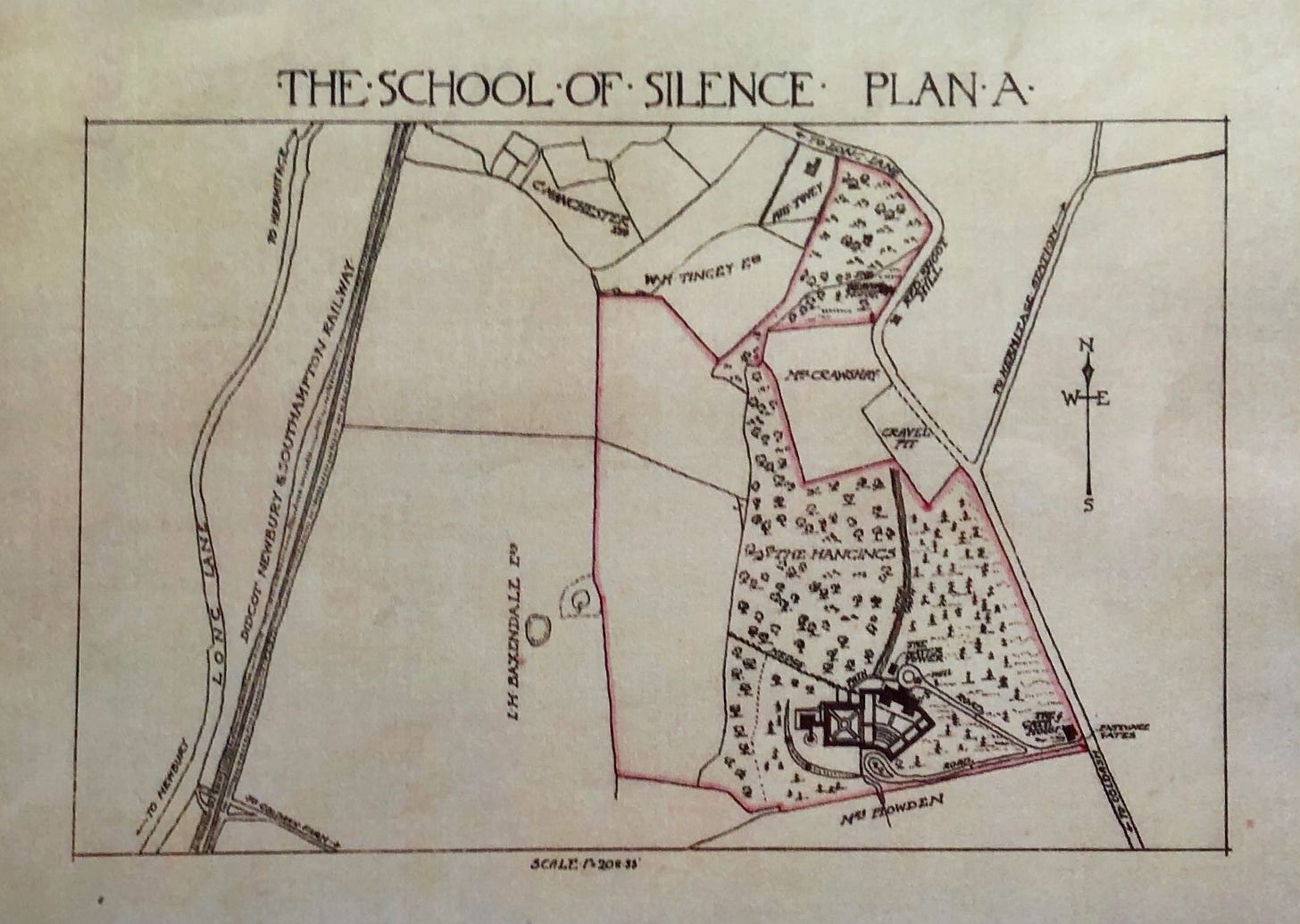

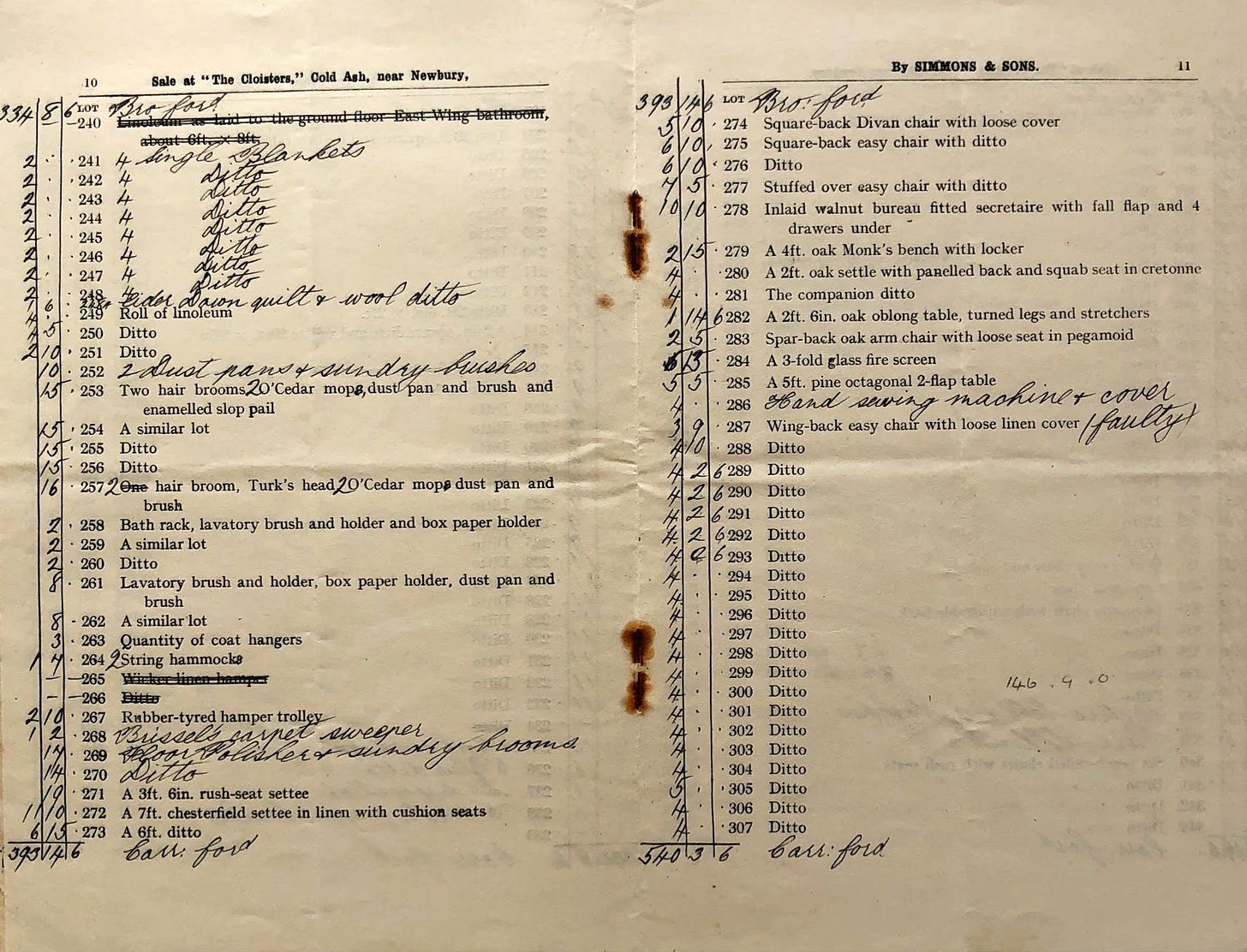

It was in 1914 that Adela Curtis embarked on her plans for a Settlement in the country, in a village called Cold Ash in Berkshire, where she had purchased 230 acres of mixed pasture and pine wood. As Phil states, ‘…there she built a large house with a chapel and cloisters, a lodge, a Greek amphitheatre and later a model farm and children’s school.’

This was intended as a training ground for others who wished to practise as teachers and healers themselves. Her vision was that the Settlement was to be a model that in time would be replicated in other parts of the country: Adela hoped her students would spread the work in this way. To this end the Order of Silence was established, with three degrees of Ministrants. In order to reach the highest level, a student would have needed a minimum of seven years in training and a significant amount of money to pay for it all and to support themselves.

It was a bold experiment, into which Adela Curtis put her heart, soul and not inconsiderable energies and it was a success for a time. Sister Unity wrote from her own experience of living at Cold Ash:

‘For the first three years the Community flourished - these were years full of wonder and enthusiasm. Visitors came from many parts of the world and, from time to time we were joined by members of the Forces on leave from France.’

By 1917, Adela clearly felt that the Settlement was achieving what she had hoped for, as in that year she produced a small pamphlet entitled A Successful Experiment in National Economy, in which she called on the nation to follow their lead and adopt self-sufficient ways of living, not just as a wartime expedient, but as a lifetime commitment. She was to say similar things at the time of WWII. Many people today would share her concerns about how we live and eat and our relationship with the land.

Sadly, cracks began to appear. The finances eventually became impossible as fewer people came to live on the Settlement. Another significant factor was that Adela ran everything herself and this was just not a sustainable model. It seems she could not delegate and she was a perfectionist - there was one way of doing things… She eventually looked for others to take on some leadership but perhaps unsurprisingly, no one was willing to do so. It is a sad irony that although Adela realised that a self-sufficient life was more possible if done in community, she wasn’t a community person herself.

I also wonder if the training/ way of life that Adela established was just too long and complex to succeed as she had hoped. As far as I am aware, no one did go on to set up their own centre as a result of their time with her. It is interesting to compare this with the experience of Marian Dunlop, the founder of the Fellowship of Meditation. She had also trained with Porter Mills, but she developed a simple approach to training others to lead meditation sessions and the Fellowship went on to have active members around the country. It still continues its work today, albeit in a smaller way.

When Adela Curtis moved to Dorset, she was quite unwell and no doubt thought her active life was over. She bought a field and lived in a WWI surplus army hut overlooking the sea and neither wrote nor taught for about five years. The failure of the School hit her hard. However, she was not completely broken and this was not the end of her story…

The Will to Understand

I finish this post with words from Howard Thurman in The Mood of Christmas and other Celebrations. His starting point is that we humans are all one and unity is in the Spirit.

The words below resonate with me in my encounters with others, both the living… and the people I study in my research, many of whom are long dead. There is much in Adela Curtis’ life and world which is unfamiliar to me and I want to understand her to do her justice in the way I write about her.

The will to understand other people is a most important part of the personal equipment of those who would share in the unfolding ideal of human fellowship. It is not enough merely to be sincere, to be conscientious. This is not to underestimate the profound necessity for sincerity in human relations, but it is to point out the fact that sincerity is no substitute for intelligent understanding.

The will to understand requires an authentic sense of fact with reference to as many areas of human life as possible. This means that we must use the raw materials of accurate knowledge of others to give strength and direction to the will to understand. [pp55,56]

Interesting that she advocated communal living but was difficult to get along with. Yes, understanding people is key. This takes a lifetime.